Lockheed Martin F-35 (JSF)

Lockheed Martin F-35 (JSF) user+1@localho… Mon, 12/20/2021 - 21:17 The F-35 Lightning II / Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) is a U.S. fifth-generation, single engine, multirole fighter developed in partnership with eight nations and produced by Lockheed...

Lockheed Martin F-35 (JSF) user+1@localho… Mon, 12/20/2021 - 21:17

The F-35 Lightning II / Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) is a U.S. fifth-generation, single engine, multirole fighter developed in partnership with eight nations and produced by Lockheed Martin. It is designed in three variants and is powered by a single Pratt & Whitney F135 turbofan engine. Each variant features a different derivative of the F135 engine. As of December 2021, more than 730 F-35s have been delivered to the U.S., international JSF partners and Foreign Military Sales (FMS) customers. Production is expected to continue into the 2040s.

Features

Low Observable Technology

All variants of the F-35 use a variety of techniques to reduce their radar cross section (RCS). Some of these techniques were used on previous low observable aircraft while others have been improved or are completely new. As with the F-22, the F-35 uses planform alignment to orient flight surfaces, fuselage facets and gaps to concentrate radar reflections into a minimum number of angles. The canopy is metalized to reduce scattering from the cockpit. Doors and access panels have sawtooth edges. Internal weapons bays allow the aircraft to carry air-to-air weapons and a small number of ground-attack weapons while keeping the ordnance shielded from radar.

The engine exhaust is also designed with low-observability to radar in mind. The nozzle consists of vanes with rear-facing facets that abut into a circular, sawtooth pattern. The outer surfaces of the vanes appear to be covered with RAM. In addition, towards the front of the nozzle, the vanes are covered by skin panels with sawtooth patterns that also adjoin with each other in a sawtooth fashion. These panels are likely radar-absorbent structures whose purpose is to reduce scattering in the gap between the vanes and fuselage around the nozzle.

Low observable technologies significantly matured between the development of the F-22 and the subsequent F-35 as shown by the F-35’s use of Diverterless Supersonic Inlets (DSIs) and improved Radar-Absorbent Material (RAM) coatings. Lockheed Martin began internal research and development on low observable Mach 2 inlets in the early 1990s which informed the X-35’s development. In the Spring of 1997, Lockheed Martin had two competing X-35 design proposals. One featured Caret inlets (used in the F-22 and F/A-18E/F) and the other used DSIs. Lockheed had demonstrated the feasibility of DSIs through flight testing of a modified F-16 in December 1997. Inlet designs of modern fighter aircraft must provide flow compression and boundary layer control such that the engine is fed high pressure, low distortion airflow across multiple flight regimes. The F-22’s 2-D Caret inlets use a boundary layer diverter and bleed system feeding into serpentine ducts to regulate airflow at the cost of manufacturing complexity and weight. Lockheed Martin studies showed incorporating DSIs would lower weight, be easier to manufacture and lower the X-35’s RCS. The F-35’s DSIs have a 3-D bump and forward swept cowl which feed into a bifurcated, serpentine duct – eliminating the need for a boundary layer diverter and bleed system.

The F-35’s RAM represents a significant improvement in signature reduction and maintenance needs when compared to the F-22 and B-2. Gaps between parts on the skin of the aircraft generate radar returns, the F-22 and B-2 solve this problem by applying a thick topcoat of RAM on top of the gaps. Lockheed Martin reduced the number of parts on the F-35’s skin and used improved manufacturing technologies (such as precision laser alignment of parts during assembly) to eliminate gaps. Lockheed Martin claims that parts fit so precisely “that 99% of maintenance requires no restoration of low-observable surfaces”. This new approach reduces the amount of RAM required, greatly lessens the airframe's need for line maintenance (by as much as two orders of magnitude compared to the F-22) and also makes the F-35's low observability features more resilient by mitigating the risk of skin abrasions. The F-35 still receives a RAM topcoat that is applied in thicker layers at high scattering areas, such as the engine inlets. The coating also reduces skin friction and drag, thereby saving fuel and likely reducing the aircraft's IR signature. Beneath the RAM-embedded material is a conductive layer that further reduces RCS by modifying the radio waves before they bounce back out through the RAM.

Avionics

APG-81 Active Electronically Scanned Array Radar

The F-35's radar, the Northrop Grumman APG-81, evolved from the APG-77 featured on the F-22A. Compared to conventional, mechanically-scanned radars, the APG-81's active electronically scanned array (AESA) delivers greater range, 1,000-times faster scanning and the ability to engage many more targets simultaneously. The APG-81 features at least 1,200 transmit receiver modules. Detection range varies with the square root of antenna size and fourth root of transmitted power. However, the APG-81 features better transmit/receive modules and improved processing than the APG-77. In 2000, a senior U.S. Air Force official predicted the JSF radar would have 75% of the detection range of the F-22’s. APG-81 capabilities include: Ground Moving Target Indication (GMTI), Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), high gain Electronic Support Measure (ESM) and Electronic Attack (EA), cruise missile detection and tracking and air-to-air multitarget detection and tracking. The APG-81 can simultaneously operate in air-to-air and air-to-surface modes. A maritime targeting mode will be installed later and is expected to include an inverse SAR mode.

AAQ-37 Distributed Aperture System

In addition to the radar, the JSF bears a unique Distributed Aperture System (DAS) that provides unmatched levels of visual situational awareness. Six mid-wave IR cameras, each weighing 16-17 lb., are situated around the aircraft to enable the DAS to see in all directions: one camera is mounted on each side of the chine line beneath the canopy, one camera is mounted in front of the canopy, one camera is mounted on the dorsal (in front of the boom refueling receptacle for the F-35A) and two cameras are mounted on the underside of the fuselage. Each camera provides a 95° field of regard, combining to form 570° overlapping coverage. The DAS informs the pilot of threats such as surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery and other aircraft. When a threat is detected, the system boxes it in the visor projection or draws the pilot’s attention to it with alert signals and lines.

Generation III Helmet Mounted Display System

The F-35 does not have a Head-up Display (HUD) like most modern fighter aircraft. Relevant flight reference, navigation and weapons employment functions which are typically displayed on a HUD are instead shown on the F-35’s Generation III (Gen III) Helmet Mounted Display System (HMDS). The HMDS supports off boresight AIM-9X shots. The pilot looks at a target through the HMDS and locks onto it. The AIM-9X can maneuver up to 90° from the aircraft’s centerline to pursue the target.

The Gen III helmet projects the feed from the DAS onto the pilot's visor, showing the image from the DAS during the day or night in whichever direction the pilot's head is turned, including down and backwards, essentially letting the pilot see through the aircraft. The Gen III helmet also bears an ISIE-11 digital night vision camera which projects its two megapixels of data at 60 hertz onto the HMDS.

AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System

The Lockheed Martin AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Tracking System (EOTS) is a mid-wave infrared sensor which provides F-35 pilots with long-range IRST, air-to-air targeting forward-looking infrared (TFLIR), high resolution forward-looking infrared (FLIR), laser designation and laser spot tracking capabilities. EOTS provides additional passive detection capability along with the ASQ-239 electronic warfare suite. The APG-81 can cue the AAQ-40 to locate and track airborne targets. The system is housed in a low observable aperture in the lower forward fuselage. Space, power and cooling constraints presented major challenges to the development of EOTS – the system occupies approximately four cubic feet and weighs 202 lbs. The EOTS is mounted right below the radio frequency support electronics of the APG-81 and is cooled with polyalphaolefin (PAO) liquid coolant in a similar manner as the APG-81.

ASQ-239 Electronic Warfare Suite

The BAE ASQ-239 Electronic Warfare/Countermeasure System (EW/CM) integrates RF and IR spectrum self-protection and ESM functions. The ASQ-239 supports: emitter geolocation, high gain EW through the APG-81, multi-ship emitter location, radar warning and self-protection countermeasures and jamming. Lockheed Martin claims the F-35’s EW systems are capable of transmitting ten times the radiated power of legacy fourth generation aircraft, enabling the F-35 to provide stand-off jamming capabilities. Pre-Block 4 aircraft have six multi-element antenna array sets covering the Band 3 and Band 4 frequency spectrum (S band for IEEE designation). Two antenna apertures are installed on the leading edge of each wing and one antenna aperture is installed next to the aft wing tip of each wing. The antenna placement for the F-35C is slightly altered to account for the F-35C’s longer-folding wing. Band 2 and 5 antennas will be installed as part of the Block 4 modernization program.

ASQ-242 Communications, Navigation and Identification System

The Northrop Grumman ASQ-242 Communications, Navigation and Identification System is an integrated avionics system which combines the following functions: identification, friend-or-foe (IFF), secure, jam-resistant and low probability of intercept communications and navigation and landing aids. The F-35 has two primary methods of communication, voice radio and data links. Radios include SINCGARS, HAVEQUICK, GUARD and VMF 220D.

The F-35’s primary data link is the Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL) which provides low probability of intercept communications between F-35s. Each F-35 within a four-ship formation can share data that one aircraft collects within the whole formation. In 2009, Chief of the USAF’s Electronic System Center Airborne Networking Division – Michael Therrian, explained MADL is a Ku-band data link which transmits a narrow beam between aircraft using a daisy chain system. The first aircraft sends the narrow beam signal to the second aircraft which in turn sends the signal throughout the rest of the formation. MADL trades bandwidth for low observability. Conventional data links like Link 16 have higher bandwidth capacity but broadcast signals which can be located by adversary electronic support measures. The F-35 can communicate with legacy platforms such as the F-15 and F-16 using Link 16 but its use will be subject to the threat environment and techniques, tactics and procedures which will be developed by the services to mitigate the limitations of Link 16.

Weapon Systems

While equipped with six external hard points (not including the centerline gun pod mount for the F-35B and F-35C), the F-35 must carry its weapons internally in two weapon bays to maintain its low observability. For strike missions, the JSF can internally accommodate two Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAMs) -2,000-lb. GBU-31s for the F-35A and C, 1,000-lb. GBU-32s for the F-35B - along with two AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles (AMRAAMs). The bay can also house the GBU-38 500-lb. JDAM, GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb I (SDB), GBU-12 500-lb. laser-guided bomb (LGBs) and AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW), as well as the U.K.'s AIM-132 Advanced Short-Range Air-to-Air Missiles (ASRAAM) and Brimstone air-to-surface missile. In the air-to-air role, the F-35 can currently accommodate four AIM-120s internally. The U.S. its close allies Australia and the UK use the more advanced AIM-120D with a maximum range of 100 nautical miles. Other operators use the AIM-120C-7 and C-8 (obsolescence modification of the C-7). A pair of AIM-9X Block IIs can be carried on LO pylons. U.S. Navy budget documents suggest the latest variant of the Sidewinder features RAM to reduce its RCS, though its sill expected to degrade the F-35's LO performance.

The F-35A carries a GAU-22/A four-barrel, 25mm cannon internally; the B and C variants have no internal cannon but can carry a reduced RCS missionized gun pod externally. Four 25mm rounds are being developed for the F-35: the ATK PGU-23 training round, Nammo’s PGU-47/U armored-piercing explosive (APEX) round for all F-35 variants, Rheinmetall's PGU-48A/B Frangible Armored Piercing round for the F-35A and the General Dynamics/ATK PGU-32 semi-armored piercing high explosive incendiary (SAPHEI-T) round for the F-35B and C. The PGU-48/U and PGU-32 rounds are specialized to defeat targets particular to the respective service. Over 3,400 rounds of PGU-23, PGU-47 and PGU-48 rounds were fired from F-35As against both ground and aerial targets. The DoD Director, Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) reported that it found “the accuracy of the gun, as installed on the F-35A, to be unacceptable”. Possible remedial actions include re-boresighting and correcting gun alignments. A total of 2,685 PGU-23 and PGU-32 rounds were fired from the missionized gun pod during tests. The DOT&E reports the gun pod meets air-to-ground contract specifications and do not share the accuracy errors of the F-35A.

In March 2018, the USAF awarded Rheinmetall Switzerland a $6.5 million contract for 40,000 rounds of PGU-48A/B rounds. In October 2018, Orbital ATK was awarded a $1.5 billion contract to deliver 332,993 rounds ammunition across multiple types – including the PGU-32.

Blocks

To support the concurrent development and early production efforts, the F-35 is being fielded in Blocks. Some blocks incorporate hardware as well as software changes. Blocks 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1A, 1B and 2A supported testing and limited training capability for early LRIP and System Development and Demonstration aircraft. Block 2B began flight testing in February 2014 and provides initial combat capabilities to the F-35 including expanded MADL capability, multi-ship sensor fusion and the carriage of two AIM-120C-7 AMRAAMs and two PGMs (either the GBU-32 JDAM or GBU-12). The USMC declared IOC on the Block 2B software in July 2015 which comprises 87% of the final code and will deliver the initial warfighting capabilities.

The Block 3i configuration forms the stepping stone for full Block 3F warfighting capability. Block 3i rehosts Block 2B software with substantial hardware changes. Block 3i includes new radar, EW and Integrated Core Processor (ICP) modules. The configuration also adds the third generation HMD which corrects the Gen II helmet’s poor night vision acuity. The USAF declared IOC with the Block 3i configuration.

Block 3F configuration represents the full warfighting capability configuration for the F-35 including:

- Full Flight Envelope: 9g maneuvering and top speed of Mach 1.6

- Full Weapon Capability of: GBU-31 1,000 lbs. JDAM, GBU-32 2,000 lbs. JDAM, GBU-39 SDB I, Joint Stand-Off Weapon (JSOW) C1, AIM-120D, AIM-9X and GAU-22 cannon

According to Lockheed Martin, Block 3F software has more than 8.3 million lines of code which is approximately four the amount of code in the F-22. Block 3F was released on late LRIP 9 aircraft during the Fall of 2017. There were 31 different versions of the Block 3F software by the end of October 2017. In December 2018, the F-35 began the Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E) phase using version 30R02 of the Block 3F software. DoD Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) Robert Behler announced that 30R02 improves the F-35’s suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD), electronic attack, air interdiction and offensive counter air capabilities. See upgrades section for additional information about future Block capabilities. Note, upgrades beyond FOC (Block 4) are discussed in the upgrades section of the profile.

Variants

F-35A

The F-35A Conventional Takeoff and Landing (CTOL) variant is the U.S. Air Force (USAF) model powered by the P&W F135-100 turbofan. The aircraft will replace the F-16 and A-10. The variant reached Initial Operational Capability (IOC) in August 2016 and by the 2030s it will constitute the bulk of the service's fighters. The F-35A can be visually distinguished by its boom refueling receptacle port on the top of the airframe and gun blister mounted on the upper port side (left from the perspective of the aircraft when facing forward).

F-35B

The F-35B Short Takeoff and Vertical Landing (STOVL) variant is the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) model, intended to replace the service's AV-8Bs on amphibious assault vessels and F/A-18s at land bases and on aircraft carriers. The design is most distinguished by its unique lift system. The F135-600 engine has a rear nozzle that can rotate downward 90 deg. for vertical thrust, while also swiveling left and right for yaw control in a hover. The engine also drives a shaft connecting it, via a clutch, to a two-stage lift fan located behind the cockpit and exhausting downward through nozzle vanes that vector the vertical thrust fore and aft. Finally, compressor bleed air is fed to nozzles in the wings to provide vertical lift and roll control. Together, these systems allow the F-35B to take off from short runways or decks and land vertically. The F-35B can be visually distinguished by its shortened canopy as a result of the lift fan. The panel lines as well as associated markings are visible from both the top and bottom of the airframe. The B variant also has two diamond-shaped roll ducts on the underside of each wing.

F-35C

The F-35C carrier variant (CV) is the U.S. Navy (USN) model, intended to provide a stealthy strike platform to complement the F/A-18 in U.S. carrier air wings. It is most distinguished by its larger wings (which include two control surfaces each instead of one on the A & C variants) and horizontal stabilizers, as well as its tailhook and reinforced landing gear. The F-35C is powered by a single F135-400 turbofan engine. USN declared its F-35C's had reached IOC in 2019. The F-35C has a diminished flight envelope with a g-limit of 7.5 when compared to 9.0 for the other variants. Like the F-35B, the F-35C lacks an internally mounted cannon.

F-35I

The IAF version of the JSF is based off the F-35A and is sometimes designated as the F-35I for its unique features and has been dubbed the Adir (Great). Israel has insisted it be allowed to install indigenous technologies on the JSF. After long deliberations, it was decided that the first squadron of F-35s will be delivered to Israel with only unique Command, Control, Communications, Computers and Intelligence (C4I) capabilities developed by Israel Aerospace Industries. The C4I system and the software will facilitate future indigenous weapon and electronic warfare capabilities. In terms of weapons capabilities, Israel has received a license to integrate Rafael’s Spice GPS/EO/IIR bomb-guidance systems. Rafael is about to complete the development of a Spice seeker and tail kit that could fit into the JSF’s weapons bays. In July 2018, Lockheed Martin and Rafael Advanced Defense Systems announced a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to market the Smart, Precise Impact and Cost-Effective (SPICE) series of PGMs. Rafael has previously expressed interest in integrating the Python 5 short-range AAM to fit into the F-35’s internal bay, the AIM-9X is currently only certified for external carriage.

Production & Delivery History

As of the time of this writing, the U.S., eight partner nations (including the U.S. as well as Canada - the later has yet to formally order aircraft) and eight FMS customers have collectively committed to field over 3,000 aircraft, though several countries have expressed interest in increasing their fleets. As of December 2021, more than 730 aircraft have been delivered. Lockheed Martin produces all F-35s at Air Force Plant 4 in Fort Worth, Texas. The facility covers over 6 million square feet with a production bay over a mile long. The company also supports two final assembly and check-out lines outside (FACO) of the United States including one in Northern Italy (Cameri) managed by Leonardo and one in Nagoya Japan (Aichi Prefecture) managed by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Lockheed Martin is currently producing F-35s under Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) lots as the DoD will not grant a full rate production (FRP) decision until the NAVAIR managed Joint Simulation Environment (JSE) is ready. In April 2021, Lockheed's CFO Kenneth R. Possenriede stated Lot 16 production was expected to be awarded in Q4 of 2021. The $9 billion order is expected to comprise a 50-50 split between U.S. and international orders. The Navy awarded Lockheed a $904 million contract to support long-lead items for 133 Lot 16 aircraft on Dec. 30, 2020.

In May 2020, Lockheed Martin announced it expected to deliver 141 F-35s in 2020, only seven more than 2019, as a result of COVID-19. The pandemic was expected to tapper production for three months by 18-24 aircraft. Lockheed Martin has not commented on which customers would be affected. However, an Australian Parliamentary Committee was briefed by the RAAF that a small number of its jets could be delayed by one or two months as a result of COVID-19. Lockheed ultimately delivered 123 aircraft in 2020, including 74 U.S. and 49 foreign aircraft (31 international partner nation and 18 FMS jets).

In June 2021, Lockheed announced it planned to deliver between 133-139 aircraft in 2021. Delays as a result of COVID-19 are now expected to persist longer than anticipated. The company had previously expected to deliver 169 aircraft in 2022 and approximately 175 aircraft a year thereafter. Lockheed had stated the peak production capacity of the FT. Worth plant was 185 aircraft per year. In September 2021, the JPO and Lockheed reached a "production smoothing" agreement to help Lockheed recover from enduring supply chain disruptions caused by COVID-19. Under the framework, Lockheed would deliver 156 aircraft per year for the next several years.

United States

The U.S. DoD estimates the entire domestic program will cost $397.7 billion, including $324.5 for procurement 2,456 aircraft (not including the construction of 18 test aircraft and six static ground test articles) for three services - 1,763 F-35As for USAF, 273 F-35Cs for USN and 353 F-35Bs and 67 F-35Cs for USMC. RTD&E outlays are expected to reach $70.07 billion over the life of the program. The JPO estimates that over their lifetimes these aircraft will require operations and sustainment (O&S) spending of $1.196 trillion. All of these figures are in FY21 dollars.

U.S. Air Force

U.S. Air Force orders alone represent approximately 50% of projected F-35 deliveries throughout the life of the program. The USAF had plans to replace 281 A-10s and more than 900 F-16s with F-35As. The service had planned to acquire 80 F-35As per year starting in 2022 but the service subsequently revised the maximum procurement rate down to 60 aircraft per year (including 48 in recent years + 12 in the unfunded priority request or UPL until FY22). The lower annual procurement rate would extend Air Force procurement by six years or from 2038 to 2044. Growing concerns over both cost per flight hour (CPFH) and Block 4 retrofit costs resulted in the USAF reducing its FY22 buy to just 48 aircraft with no additional aircraft in the UPL. Going forward, the performance of LM's proposed sustainment strategy and rollout of Block 4 into the mid-2020s is expected to impact the overall POR and forthcoming USAF and Joint Staff future tactical aircraft (TACAIR) study which is expected to be completed by the summer of 2021.

Since at least 2018, the Air Force has become increasingly concerned with the F-35A's high cost per flight hour (CPFH) as well as broader sustainment issues affecting the type such as its mission capable (MC) rates, cost per tail per year, etc. CPFH figures vary widely due to different methodology and the base year from which they were tabulated. The F-35's CPFH figures are often measured in FY12 constant dollars as that is when the program was rebaselined or in then year (TY) dollars when adjusted U.S. DoD operations & maintenance account deflator values. For example, according to CAPE, the F-35A's CPFH of $44,000 in TY2019 compared to the F-16's $22,000. The F-35 lifecycle sustainability plan (LSP) that was approved in January 2019 highlights eight lines of effort that assess cost per flying hour, cost per tail per year and overall ownership cost, according to former F-35 program executive officer Vice Adm. Mat Winter. In Feb. 2021, Air Combat Command's Gen. Mark Kelly expressed skepticism that LM would be able to lower that figure to FY12 $25,000 ($29,036) by 2025 under the proposed performance based logistics contract (PBL). Lockheed Martin reduced the cost per flying hour by 15% from 2015-2019 and another 18% from 2019-2021. However, to achieve the $25,000 flight hour goal, LM, the USAF and P&W would have to make cumulatively reduce costs by more than 30%.

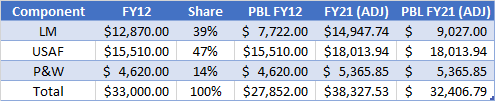

Lockheed’s plan for addressing concerns about the F-35A’s hourly operating costs includes a major limitation. As the airframe supplier, Lockheed directly controls only 39% of the F-35A’s hourly operating cost, a company official said (as shown in the table above). By contrast, the Air Force controls about 47% of the cost. The F135 engine supplier, Pratt & Whitney, is responsible for the last 14%. In absolute terms, that means the Air Force’s share of the $33,000 CPFH (FY12) comes out to $15,510. Lockheed’s share is $12,870, leaving P&W with $4,620 of the total bill.

By using a variety of tools, including an emerging, supply-based performance-based logistics deal and the opening of repair depots, Lockheed believes it has a solid plan to reduce the airframe portion of the cost per flight hour by 40% by the end of fiscal 2025. Since the company’s cost-saving plan only applies to its $12,870 share of the overall hourly cost, a 40% reduction would reduce the F-35A’s hourly cost attributable to the airframe by only $5,148, lowering Lockheed’s share of the overall total to $7,722 (table above also includes notional FY21 adjusted PBL values).

In absolute terms, Lockheed’s plan, if realized, would reduce the cost per flight hour of the F-35A to $27,852, which is still $2,852 higher than the company’s commitment. To hit the $25,000 (FY12) target by the end of fiscal 2025, Lockheed needs help from the Air Force and Pratt, which account for $20,130 of the $33,000 hourly cost. Fortunately, neither would be required to match Lockheed’s plan to cut its share of the cost by 40% over the next 4.5 years. Instead, the Air Force and Pratt would need to reduce their costs by only 14.2% to match the overall, $25,000 cost goal. In September 2021, Lockheed Martin was awarded F-35 PBL worth up to $6.6 billion. The contract is structured over FY21, FY22 and FY23 in one year option segments. CPFH could drop by 8% over the period to $33,400 in 2023.

The Air Force is evaluating “levers” to reduce its share of the F-35A’s hourly operating cost, Gen. Charles Brown, Air Force chief of staff, said in Congressional testimony in early June. But the Air Force’s options are constrained in some cases by enterprise-wide interests. For example, Lockheed has outlined a seemingly straightforward path for the Air Force to achieve a roughly 33% manpower cost reduction for line maintenance: By cross-training maintainers on multiple systems, the Air Force could cut the number assigned to each F-35A to nine from 12. However, that proposal may require the Air Force to bifurcate a common pool of aircraft maintainers, creating separate training and career pipelines for the F-35A and the rest of the fighter fleet.

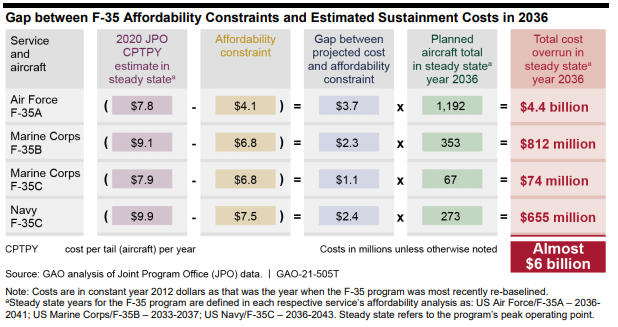

Another core sustainment metric aside from CPFH is cost per tail per year (CPTPY) - the overall sustainment cost for the whole fleet divided by the number of aircraft in service. CPTPY is an important complementary metric to CPFH because the latter is highly variable with the total number of flight hours. For example, increasing flight hours decreases CPFH but would increase total sustainment costs as reflected by CPTPY. An April 2021 GAO report (above) highlighted the significant discrepancy in actual CPTPY costs above USAF projections in FY12 dollars. Notably, GAO's analysis is somewhat limited by taking current costs and projecting them forward. In practice these metrics (MC, CPFH, CPTPY) all vary with production lot. Subsequent lots have generally shown better reliability (mean time between failure) of components and greater availability including fewer man hours in maintenance.

However, the net effect of these growing sustainment concerns has put significant pressure on the 1,763 POR as the service would not be able to sustain that fleet at current CPFH metrics. Additionally, the service appears to be recalibrating its assessment that only fifth generation fighters could participate in Day 1 actions against near-peer threats. Created in January 2018 as an internal think-tank, the Air Force Warfighting Integrating Capability (AFWIC) office had torn up the long-standing assumption that only stealthy fighters could perform a useful role in the future. By the end of 2018, the AFWIC’s team of analyst had adopted a new fighter roadmap which envisioned a great power war. The principal role for each F-35A was to launch two stealthy cruise missiles — Lockheed’s AGM-158 JASSM — from just inside defended airspace. That “kick-down-the-door” pairing would be combined with mass launches of multiple JASSM each from F-15Es and F-15EXs, the source said. Other missions — namely, defensive counter-air and homeland defense — could be performed by the F-35, but other aircraft, such as F-15EXs and F-16s, also could be used. Driven by this new appreciation for a portfolio of fighter capabilities, the AFWIC team also reconsidered how many of each type would be needed. AFWIC’s fighter roadmap by the end of 2018 had capped F-35A deliveries at about 1,050 jets. If new aircraft orders are maintained at a rate of two to 2.5 squadrons a year — between 48 and 60 jets — for the foreseeable future, the Air Force is at least 10 years away from hitting the 1,050 cap in AFWIC’s fighter roadmap.

In the meantime, the Air Force faces other decisions about whether to invest in more fourth-generation fighters, F-35As or next generation aircraft. The Air Force still operates 232 F-16C/D Block 25 and Block 30 jets, which were delivered in the mid-1980s. Air Force officials have said they expect to make a fleet replacement decision for these so-called “pre-block” F-16s in four to seven years. When the Air Force established the program of record for buying 1,763 F-35As, the plan assumed replacing all of those pre-block F-16s. As a replacement decision enters the DOD’s five-year budgeting horizon, however, Air Force officials have been more flexible. In February 2020, the head of Air Combat Command, who was then Gen. Mike Holmes, said that low-cost, attritable aircraft would be considered for the pre-block F-16 replacement in the 2024-2027 timeframe. Discussions of a FT-7 (modified Boeing T-7A Red Hawk) or new build F-16 Block 70 were also reportedly discussed as options. In February 2021, Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Brown announced CAPE would conduct a tactical combat aircraft (TACAIR) study for its future force structure. A "clean sheet" 4.5 generation aircraft would be evaluated as a potential option according to Gen. Brown. In May 2021 as part of its budget rollout, the Air Force revealed plans to replace the 600 "post-Block" F-16s by the prospective multi-role fighter (MR-X) or the F-35 should its sustainment metrics improve.

Even if the Summer 2021 TACAIR study validates the full 1,763 POR, a bow wave of modernization priorities in the mid-2020s into the early 2030s may force the USAF to reduce its buy of F-35s. The USAF's FY22 aircraft procurement budget was $15.7 billion of which $3.76 billion was for the modification of in-service aircraft and $9.74 billion for new build aircraft (remainder on spares, infrastructure, etc.). By mid-decade the USAF aircraft procurement account will be under enormous strain to fund at least five B-21s annually at FRP worth more than $3.4 billion, as well as T-7A FRP, KC-46 FRP, HH-60W FRP, MH-139 FRP and 72 TACAIR platforms per year (F-35 & F-15EX). If trends continue, the USAF would need more than a 30% higher procurement budget for new build aircraft than its FY22 request. The budget outlook becomes even more bleak later in the decade as NGAD RDT&E reaches its apex and transitions to production, MQ-Next enters service around 2031 and KC-Y (KC-46 follow-on) also enters service. Thus, the USAF has a narrow window in the 2020s in which it is able to afford to buy 60 F-35As per year to recap its legacy TACAIR platforms before the wave of next generation platforms enter service. If the USAF buys 60 F-35As per year through 2030, the USAF would reach the 2018 AFWIC figure of 1,050 airframes

The FY22 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) included a number of measures to correct the trajectory of F-35 O&S efforts across the services and re-align procurement. The bill mandates each of the services to generate CPTPY figures by October 1st, 2025 which will come into force by FY2027. If any variant is unable to meet the CPTPY, procurement could be proportionally reduced. Perhaps most significantly, the JPO would transfer all O&S responsibilities to the respective services by FY2028 followed by all acquisition responsibilities by FY2030. The bill also requests an acquisition strategy from the Secretary of the Air Force and Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to outfit the F-35A with an adaptive cycle engine by FY2027. The NDAA discusses the prospect of B and C model engine upgrades.

Department of the Navy

Cumulatively, the USN and USMC plan to buy 693 F-35s including 353 Bs and 67 Cs for the USMC as well as 273 C models Navy. These aircraft will be procured into the early 2030s to replace the legacy Hornet and AV-8 Harrier. The Navy's slow induction of F-35Cs and expansion of its Super Hornet POR has effectively meant legacy hornets in carrier air wings have already been replaced. The FY22 budget request's UPL adds five F-35Cs for $535 million, increasing C model procurement from 15 to 20 if authorized. The Navy will operationally deploy F-35Cs for the first time in 2021 from the USS Carl Vinson.

As of the time of this writing, the USMC's POR for 353 Bs and 67 Cs remains in flux. U.S. Marine Corps Commandant Gen. David Berger may alter the service’s POR as a result of an external review following the “Force Design 2030”. The wide-reaching for structure plan recommended cutting the number of F-35s per squadron from 16 to 10 while maintaining a requirement for 18 fighter/attack squadrons. The external study will re-evaluate the USMC’s existing F-35 POR. The latest Selected Acquisition Report current as of the FY2021 PBR does not alter the USMC’s POR.

Australia

Australia has a program of record for 72 F-35As which will be delivered by August 2023. A fourth squadron is being considered which would increase the fleet to 100 aircraft. Australia established the AIR6000 program in 1999 to study the replacement of its Legacy Hornet and F-111 Aardvark fleets. Australia joined the JSF program as a level three partner in 2002.

In December 2021, the Australian Audit Office reported the nation's total F-35 acquisition cost is AU$15.63 billion ($11.1 billion), including payments for RDT&E contributions, aircraft procurement, military construction, weapons and training under the AIR 6000 program. Australian F-35A procurement under the AIR 6000 program is divided into two phases: 14 aircraft under Phase 2A/2B Stage 1 and 58 aircraft under Phase 2A/2B Stage 2. The roll-out of the first two aircraft occurred on July 24, 2014 and the first aircraft took flight on Sep. 29. As of December 2021, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has taken delivery of 44 airframes. The RAAF is the first international customer to receive Block 3F airframes. First arrival in Australia is occurred in December 2018 with an IOC of December 2020 and FOC in December 2023. The RAAF considers the addition of maritime strike capability critical toward the FOC. One of the squadrons will be based at RAAF Tindal, with the remainder at RAAF Williamtown. Canberra will spend AUS$1.5 billion upgrading those bases as part of the F-35 acquisition.

On Dec. 17, 2014, the JPO announced Australia would be one of the countries in the Pacific region to host heavy airframe and engine maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade (MRO&U) work. In February 2015, the Australian Minister of Defence announced BAE Systems Australia and TAE Aerospace will be assigned to support regional depot maintenance for airframes and engines respectively. The U.S. Government assigned depot level work for 65 components in November 2016. BAE Australia, Northrop Grumman Australia, RUAG and GE Aviation Australia will perform maintenance for 64 out of 65 components for the Asia-Pacific. In August 2017, the U.S. announced BAE Systems Australia will provide the Asia-Pacific F-35 Regional Warehouse capability as part of the F-35 Global Support Solution. The warehouse will be located in Williamstown and will manage the organization and provision of spares for multiple F-35 operators in the Asia-Pacific region. Total Australian industry participation in the F-35 program exceeds A$1 billion ($720 million in 2018 U.S. dollars) by the end of 2018 with A$5-9 billion expected over the program ($4.31-6.47 billion).

In December 2018, RAAF Air Marshall Leo Davies said Defence had planned to request the 28-additional aircraft in the early 2020s. Air Marshall Davies suggested Australia may wait longer – likely as a result of the major changes expected through the Block 4 follow-on modernization program. Australia’s DWP update released in July 2020 outlines plans for “additional air combat capability” between 2025 and the early 2030s valued at A$4.5-$6.7 billion ($3.1-$4.65 billion). In March 2021 interview with ASPI, Air Marshall Hupfeld was non-comital on a follow-on F-35 order, "We look at all options...What’s the sixth generation of airpower going to look like when we decide on the next round of F-35s? Is F-35 still valid if there’s a sixth-generation aircraft? Will sixth-generation air combat capability be an aircraft? I don’t know the answer to that, but they’re the things I keep my eyes open for. The [uncrewed] loyal wingman is an example of what may be part of the solution when we look at the next phase of our air combat capability program. And I’d never say never to any of those". As of the time of this writing, Australia remain supportive of Boeing's Air Power Teaming offering but has yet to formally commit toward fielding the aircraft operationally.

Belgium

In October 2018, Belgium officially selected the F-35 as the victor of its international fighter competition. Belgium was the last of the European Participating Air Forces (EPAF) nations to choose the F-35 to replace its F-16 fleet. The Defence Ministry reports the total cost of the acquisition of 34 F-35As as well as training and associated military construction costs total €4 billion ($4.5 billion in 2019 dollars) by 2030. The DSCA notification issued in January 2018 included a $6.53 billion estimated cost for the acquisition of the aircraft, related equipment and support services. The Defence Ministry estimates the total cost of the aircraft throughout its projected 40-year service life will reach €12.4 billion ($14.1 billion in 2019 dollars).

The competition originally included the Dassault Rafale, Saab Jas 39 Gripen, Boeing F/A-18E/F, Eurofighter Typhoon and Lockheed Martin F-35A. In 2017 both Saab and Boeing withdrew from the competition citing requirements which reportedly favored the F-35. Dassault was disqualified by not responding to the Request for Proposals (RFP). Instead, the French Defense Minister sent a letter outlining a broader industrial and diplomatic partnership conditional on the sale of the Rafale. The F-35 and Eurofighter Typhoon were subsequently left as the only qualifying bids.

Canada

Canada first joined the JSF program as a tier three partner in February 2000, contributing $150 million ($222.6 million in 2018 dollars) toward its development. Canada had planned to purchase 65 F-35As to replace its CF-18 Hornet fleet. In September 2015, Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau campaigned that he would withdraw Canada from the F-35 program and hold a competition excluding the F-35. Canada’s 2017 Defence Policy Report outlined that an open competition would be held to replace the CF-18 with 88 new fighter aircraft. In October 2016, Ottawa announced its intention to purchase 18 F/A-18E/F Super Hornets as an interim fighter to bridge this gap. However, trade disputes between Boeing and Bombardier effectively canceled the purchase. Canada will now acquire 18 retired RAAF Hornets as an interim fighter, but the aircraft are approximately the same age as Canada’s existing CF-18 fleet.

Eligible suppliers for the $11 billion Future Fighter Capability Project (FFCP) submitted bids in 2019. In May 2019, the U.S. Government was in discussions with Canada regarding FFCP bid language which would require all competing firms to guarantee Canadian businesses 100% of the value of the deal in economic benefits. The U.S. Government took issue with the economic offset clause as written as it would exclude the F-35 and violate Canada’s prior commitments as a F-35 partner nation. Canada ultimately modified the language of the bid to allow Lockheed Martin to participate. In November 2018, Dassault reportedly withdrew from the competition as a result of information security requirements. France is not part of the Five Eyes intelligence agreement. Dassault’s withdrawal leaves the Saab JAS 39 E/F, Boeing F/A-18E/F and Lockheed Martin F-35. Canada is subsequently disqualified Boeing's bid on December 1st, 2021. The country is expected to announce source selection by March of 2022 and deliveries expected to run between 2025 and 2031.

Denmark

Denmark first jointed the JSF program as a tier three partner in 2002. In June 2016, Denmark selected the F-35 as its preferred replacement for its fleet of 44 F-16s which first entered service in in 1980. The Defense Ministry projects a total program cost of 66.1 billion kroners or $10 billion in November 2018 dollars for 27 F-35As. The acquisition cost is reportedly 20 billion Danish Krone or $3 billion in 2019 dollars. In a April 2021 rollout ceremony, Denmark's first F-35A was presented. The first six aircraft will go to Luke AFB, AZ, training. The aircraft will be subsequently based in Denmark between 2022-23 and with the last F-35A to to be delivered by the end of 2024.

On April 14, 2014, Denmark issued request for information to Lockheed for the F-35A but also requested information on the F/A-18F, Typhoon and JAS 39E/F. Responses were due July 21, 2014. That month, Sweden's FXM defense export agency decided not to make a formal offer of the JAS 39E/F, believing the competition was biased toward favor of the F-35A. In a report discussing the Government’s reasoning for choosing the F-35, the Danish Ministry of Defence concluded that Lockheed Martin’s bid was superior to both Boeing and Eurofighter’s bids in terms of strategic, military, economic and industrial aspects. A key finding of the MoD was the F-35’s airframe is built to last 8,000 flight hours when compared to 6,000 for both the Eurofighter Typhoon and F/A-18E/F. Therefore, a smaller number of F-35s could be procured to meet the same mission demands i.e. 28 F-35As compared to 34 Eurofighters and 38 F/A-18E/Fs. The procurement was subsequently curtailed to 27 F-35As.

Finland

On December 10, 2021, Finland announced its intent to acquire 64 F-35A Block 4s upon completing the HX competitive evaluation process. Like Norwegian aircraft, Sweden's F-35s will be fitted with brake-parachutes. Deliveries will get underway in 2025 to support training in the U.S, Finnish F-35s will arrive in-country in 2026 and the type will replace the Finnish Air Force’s McDonnell Douglas F/A-18 Hornets between 2028 and 2030. “This decision will have a strong impact on the Defense Forces operational capability,” said Antti Kaikkonen, Finland’s defense minister, announcing the decision alongside Prime Minister Sanna Marin on December 10. The F-35, Kaikkonen said, would “define Finnish Air Force’s combat capability through into the 2060s.” Helsinki’s decision comes on the back of Switzerland’s selection of the same aircraft in July and means that the F-35 has been successful in virtually every fighter contest it has participated in Europe. “We are honored the Government of Finland through its thorough, open competition has selected the F-35, and we look forward to partnering with the Finnish Defense Forces and Finnish defense industry to deliver and sustain the F-35 aircraft,” said Bridget Lauderdale, Lockheed Martin’s general manager of the F-35 program. Defense officials scored F-35 as the best based on the air, land and sea scenarios posed to the bidders, although no details of the scoring system or what the other bidders achieved was revealed. The F-35 was also deemed to have the highest operational effectiveness and the best development potential.

Helsinki plans to sign the Letter of Offer and Acceptance for the Foreign Military Sale in the first quarter of 2022. Finland had budgeted €10 billion for the procurement, with the Finnish Parliament approving the use of €9.4 billion.

The breakdown of costs includes €4.7 billion for the aircraft, equivalent to €73.4 million ($83 million) for each of the 64 aircraft. Air-to-air missiles package is valued at €754 million, while the maintenance equipment, spare parts, training equipment and initial maintenance for the first five years of operations will cost €2.92 billion. Officials have put aside €777 million for infrastructure construction and project costs, while €823 million is available for additional contracts, and amendments, as well as future buys of weapons. They also note that the operating costs are well within the threshold of 10% - €254 million - of the annual defense budget, with officials noting the type’s operation “is possible with the resources of the Defense Forces. “None of the bids were significantly cheaper in terms of operating and maintenance costs,” defense officials said. The Lockheed aircraft scored 4.47/5.0, the next best package scored 3.81 - likely the Boeing F/A-18E/F & EA-18G.

Finland envisages arming its F-35s with the AIM-120 AMRAAM and AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles, Small Diameter Bombs, Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bomb kits, the Kongsberg Joint Strike Missile and the JASSM-ER cruise missile. Procurement officials say the F-35’s maintenance will be based on a solution modified from F-35's global maintenance system, adding that the proposed system meets domestic security of supply requirements. Finland’s non-aligned status means it cannot rely on allies in wartime like other operators of the F-35 can. Lockheed Martin says Finland will be able to rely on the F-35’s Global Support Solution but it will work to enable Finnish industry to undertake the repair of around 100 critical components so that the fleet can be supported if Finland becomes isolated in the event of a conflict. There will also be additional stockpiles of F-35 spares in Finland. Lockheed Martin says it will provide work for Finnish industry which will last up to 20 years. Among the companies to benefit is Patria who will build 400 forward fuselages for the wider program. Kaikkonen said the contest was tough, and “there can be only one winner, adding: “I would like to stress that all countries involved, are very close and valued partners for Finland, they continue to be so. “Our cooperation with all of them is based on long term partnerships, mutual trust and common security interests,” Kaikkonen added.

Israel

The Israeli Air Force (IAF) is on contract to receive 50 F-35s. These aircraft are referred to both as F-35As and F-35Is depending upon the source as Israeli aircraft feature unique modifications. Jerusalem purchased a first batch of 19 JSFs for $2.75 billion in 2010. These aircraft are being produced as part of LRIPs 8, 9 and 10. The first two aircraft were delivered in December 2016, the IAF declared IOC a year later in December 2017. In November 2014, the Israeli Defense Minister concluded terms for a $4.4 billion contract for 31 additional F-35s. However, the proposal ran into unexpected resistance in the Israeli cabinet, in which the Intelligence Minister raised concerns about the aircraft's capabilities and the Finance Minister raised concerns about cost. The IAF and Defense Ministry rejected the Intelligence Minster's concerns as "old and irrelevant" and stated the alternatives to additional F-35s would cost more.

On Nov. 30, the cabinet voted to purchase 14 aircraft in the second batch under a $2.8 billion contract that will also cover two additional simulators and spare parts for the fleet of 33. On November 27, 2016, Israel's cabinet approved exercising the option to procure an additional 17 F-35s for a total of 50 aircraft. In February 2018, the DoD announced a $147.96 million contract to deliver Block 3F+ upgrades to the IAF. These upgrades will enable Israeli specific hardware and software modifications.

In December 2018, IAI opened a new production line for outer wing sets which will deliver kits starting in 2019. A total of 700 wing kits will be manufactured during the first phase, IAI is expected to produce 811 pairs of wings by 2034. Israeli industrial participation in the F-35 program is expected to reach $2.5 billion by the 2030s. Israel was originally included within the European MRO&U zone for depot level overhauls, but Israel has insisted that it will field its own local depot level MRO capability for its F-35 fleet.

As part of an offset agreement related to the UAE's potential F-35 acquisition, Israel has expressed interest in an additional squadron of F-35As which would bring its total fleet to 75 aircraft. Furthermore, Israel is reported to have obtained greater access to modify its aircraft as part of the offset deal. The first instrumented F-35I test aircraft arrived in Tel Nof Air Force Base in November 2020.

Italy

On June 24, 2002, Italy joined the JSF as a Level II partner and contributed $1 billion toward the development of the program. Rome currently plans to acquire a total of 60 F-35As and 15 F-35Bs for its air force, the Aeronautica Militare (AM). The Italian Navy will acquire 15 F-35Bs. As of December 2021, 14 F-35As and one F-35B have been delivered to the AM and three F-35Bs has been delivered to the Italian Navy.

Rome originally planned to acquire 131 F-35s (69 F-35As and 60 F-35Bs) to replace its IDS Tornado, AMX light combat aircraft and AV-8B Harriers. In February 2012, Defense Minister Giampaolo Di Paola announced cuts to the F-35 program as part of a broader effort to enact defense spending cuts. The center-left Democratic Party called for further cuts to the F-35 program in 2014 which did not materialize. In 2018, Italian participation in the F-35 program was threatened by the Five Star Movement which campaigned to withdraw from the program entirely. In June 2018, Defense Minister Elisabetta Trenta clarified that the Government would continue the acquisition of 90 F-35s. However, the government would not seek additional aircraft beyond 90 and the procurement of aircraft may be slowed to reduced Italy’s financial burden.

Italian industry is the largest contributor to the F-35 program outside of the U.S. and UK. Italian industrial participation in the F-35 program broadly falls within three categories: (1) final assembly of aircraft, (2) manufacture of components for the global supply chain and (3) depot level sustainment responsibility for Europe. Italy maintains one of two Final Assembly and Check Out (FACO) lines outside of the U.S. The Cameri plant was built between 2011 and 2013 at a cost of €795.6 million euros ($900 million in 2018 dollars). The facility covers approximately 101 acres (4.4 million square feet) – including more than one million square feet of covered workspace, and contains 11 assembly stations and five maintenance, repair, overhaul and upgrade (MRO&U) stations. The Cameri FACO line is responsible for the assembly of 90 Italian F-35s and 29 F-35As from the Netherlands. Additional work may materialize from other European operators. On September 7, 2015, Italy’s first Cameri build F-35A took flight. On October 25, 2017 Italy’s first F-35B took flight.

Leonardo will manufacture 835 complete wing sets at a rate of 66 per year. Leonardo will also provide electronic warfare components, ejection seat firing mechanisms, landing aids and EOTS vacuum cell. MRO&U responsibilities include depot level repair of more than 500 F-35s from the UK, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Turkey and forward deployed USAF aircraft in Europe (two Air Force squadrons will be based in RAF Lakenheath starting in 2021).

Japan

Japan plans to acquire 147 F-35s, 105 F-35As and 42 F-35Bs, which would make it the largest operator outside the U.S. Tokyo announced its initial acquisition of 42 aircraft in 2011. In December 2018, the Defense Ministry requested an additional 105 F-35s as part of its Mid-term Defense Plan (FY2019-2023). The associated DSCA release was announced on July 9, 2020, with an estimated value of $23.11 billion including associated equipment and support services.

In December 2011, Tokyo announced plans to purchase 42 F-35As to replace its F-4EJ Kai fighters as part of its F-X program. In May 2012, the DSCA issued a notification regarding the potential sale of 42 locally F-35As as associated equipment and support services for $10 billion. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ (MHI) Final Assembly and Check Out (FACO) facility in Nagoya is responsible for the assembly of 38 aircraft. The first four aircraft were included in LRIP 8 and produced in Lockheed Martin’s Fort Worth facility. Four aircraft were included in LRIP 8 and were delivered in 2017. As of December 2021, Japan has taken delivery of 28 F-35As but lost a single aircraft in April 2019.

In May 2014, Tokyo began construction of a FACO in Nagoya and plans to load the first major subcomponents on the EMAS by the end of 2015. Japan's fifth F-35A is was first aircraft to roll off the Nagoya assembly line in June 2016. On Dec. 17, 2014, the F-35 JPO announced Japan would be one of the countries in the Pacific region to host heavy airframe and engine MRO&U work for the aircraft. Initial airframe work will begin no later than 2018 and heavy engine work no later than 2023.

As part of its FY2019-2023 Mid-term Defense Plan, the Defense Ministry announced its intent to procure an additional 105 F-35s, including 42 F-35Bs. A total of 45 F-35s will be procured over the Mid-term Defense Plan. Japan's first squadron of F-35Bs will operate from Nyutabaru air base on Kyushu starting in 2024 with six aircraft. The STOVL aircraft eventually operate off Japan’s two 27,000-ton Izumo-class ships which will be modified to serve as aircraft carriers. Japan's 2020 Defense White Paper explained:

"...out of the 45 air bases and other airfields (including those that are co-used with civilian aircraft; excluding heliports) across Japan that are used by the GSDF, MSDF and ASDF, only 20 have a runway with a length of 2,400 meters [7,800 ft.], which is usually used by fighter aircraft possessed by the ASDF. In particular, in the Pacific Ocean, there is only one such air base, the one on Iwo To, which means that the SDF has limited operational infrastructure in the region. In this respect, generally speaking, fighter aircraft capable of Short Take-off and Vertical Landing (STOVL) are expected to be able to take off from a runway with a length of around hundred meters. In theory, such fighter aircraft can take off from and land at almost all air bases and airfields (45 locations) used by the SDF".

The additional 63 F-35As will replace 99 pre-Multi-Stage Improvement Program (MISIP) F-15J/DJs. The Ministry of Finance had pushed for all 105 aircraft will be acquired directly from Lockheed Martin’s Fort Worth Plant rather than the Nagoya FACO facility to save costs, but all 105 aircraft will now be built at Nagoya as of December 2019. The Japanese government estimates the 105 additional F-35As will cost ¥1.2 trillion ($10.8 billion) to procure and will have a total lifecycle cost of ¥5-6 trillion ($45-54 billion) over a period of 30 years.

Netherlands

On September.17, 2014, the Dutch government announced it had selected the F-35A as the country's next-generation fighter to replace the F-16. Parliament ratified the purchase on Nov. 7. The government originally planed to order 37 fighters and budgeted €4.5 billion (US $5.2 billion in 2019 dollars) for the purchase. At least 29 of Denmark’s F-35s will be assembled at Leonardo’s Cameri facility in Northern Italy. In September 2018, Minister of Defence Ank Bijleveld and State Secretary for Defence Barbara Visser removed the €4.5 billion price ceiling for its F-35 procurement program. Subsequent reporting indicates the Royal Netherlands Air Force (RNAF) is seeking funds for an additional 30 F-35As to fully replace its fleet of 67 F-35As. In October 2019, the Netherlands approved the purchase of nine additional F-35As for €1 billion ($1.1 billion). As of the time of this writing, the RNLAF operates 23 aircraft with a POR for at least 46 aircraft.

Norway

In November 2008, Norway selected the F-35 as its replacement for the F-16. A total of 52 aircraft will be acquired through 2024 with a total program cost of NOK248 billion ($28.9 billion in 2018 dollars) throughout the aircraft’s service life. The Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNAF) declared IOC for its F-35 fleet in 2019 with FOC planned in 2025. As of December 2021, Norway has taken delivery of 34 F-35As.

The most significant difference in the Norwegian version of the F-35 is the addition of a brake parachute so that the aircraft can decelerate faster on Norway's runways in winter conditions. The modification requires changes in the construction of the rear fuselage section creating a compartment to hold the parachute system. On top of this is a large canoe fairing, which will open on landing. Despite its large size, the fairing has been designed to minimize impact on RCS, fitting between the two vertical tails. The addition of the brake chute also requires modifications in the cockpit to deploy it on landing. When the brake chute is not needed, the fairing can be removed. The compartment for the chute could potentially be used for other systems in the future. Canadian firm Airborne Systems is developing the braking parachute, and interest has been shown in the system by Canada and the Netherlands. Norway conducted tests of the parachute system in February 2018.

Oslo also plans to equip its JSFs with the Joint Strike Missile (JSM), a long-range ground attack and anti-ship weapon. The 900-lb. weapon is being developed from the Kongsberg Naval Strike Missile (NSM) now in service with the Norwegian and Polish navies but adapted to fit into the weapons bay of the F-35A and F-35Cas well as be carried externally. The F-35 could potentially carry up to six JSMs each. On July 2, 2014, the government signed a NOK1.1 billion ($180 million in 2014 dollars) contract with Kongsberg Defense to finish development of the missile and prepare it for integration. The company hopes to complete development in 2017. The Norwegian MoD says other countries have shown interest in integrating the missile on their F-35s. One of them, Australia, may conclude an agreement before summer 2015. Raytheon has also teamed with the Norwegian company to offer JSM to meet a U.S. Navy requirement for an air-launched anti-ship missile.

Norway's F-35s will primarily operate from a single base at Orland, on the coast near the city of Trondheim. The force will be made up of two large front-line squadrons, compared to three currently flying the F-16. In addition, four of Norway’s aircraft will remain in the U.S. to support pilot training while a further three will be stationed at Evenes, near Narvik in the far north, where they will hold NATO’s quick reaction alert to intercept possible Russian aircraft flying down into the North Sea.

Oslo is spending NOK619 million ($96 million in 2014 dollars) on new facilities for the aircraft. The facilities will include eight full mission simulators, with the intent that pilots in the will be able to synthetically train with their colleagues flying the real aircraft. The Royal Norwegian Air Force (RNAF) wants to achieve around 40% of its training synthetically compared to 20% on the F-16 currently. The airfield itself will be subjected to higher security, with new fences and earth berms to keep prying eyes out, in a bid to meet U.S. security requirements.

Poland

On May 28, 2019, Polish Defense Minister Mariusz Blaszczak confirmed plans to purchase 32 F-35As to replace its older Soviet era fighters. As early as 2016, the Polish MoD was looking at a replacement for its Su-22 and MiG-29 fleets. Subsequent studies led the MoD to conclude that Poland’s next generation fighter must be a low observable platform. On September 11, 2019, the DSCA issued a notification regarding the potential sale of 32 F-35As as well as associated equipment and support services valued at $6.5 billion. Lockheed Martin has stated it will deliver the first four F-35As to Poland in 2024 from Lot 16 production. The aircraft will be of the Block 4 configuration. A full squadron of 16 F-35As would be delivered by 2026. The next batch of 16 would be delivered by 2030.

South Korea

On March 24, 2014, Seoul announced its long-held intent to purchase 40 F-35As. On Sep.24, it announced it had completed negotiations with the U.S. government regarding price, offsets and technical details. The acquisition will cost 7.34 trillion won ($6.98 billion in 2018 dollars), according to the local Yonhap news agency: 66% for aircraft, 26% for integrated logistics, and 8% for weapons and facilities. The budget includes one spare Pratt & Whitney F135 engine. In March 2018, the first South Korean F-35 was unveiled to the public. As of July 2020, 24 aircraft are in ROKAF service. The aircraft began arriving at Cheongju AFB, South Korea, in 2019. Deliveries are scheduled to conclude by the end of 2021.

South Korea selected the aircraft to fill its F-X Phase 3 Requirement in December 2013 due to strong support from the Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) and there is a strong possibility the fleet will grow beyond the currently planned size. The F-X Phase 3 program was allocated only 8.3 billion won ($7.9 billion in 2019 dollars), which is forcing the country to procure only 40 F-35As instead of the 60 intended for the program. ROKAF is known to want a second batch of another 20 F-35As. The service had avoided pushing for it, perhaps because doing so would put more budgetary pressure on the KF-X program to produce at least 120 indigenous 4.5 generation fighters.

Singapore

On December 18, 2019, Defence Minister Ng Eng Hen announced the Defence Science and Technology Agency and the Republic of Singapore Air Force had evaluated the F-35 as the most suitable replacement for its F-16C/D Block 52 fleet. Defence Minister Hen “We will procure a few planes first, before deciding on a full fleet”. Singapore initially did not announce which variant it had selected and was understood to be evaluating both the F-35A and F-35B. On January 9, 2020, the DSCA issued a notification regarding the potential sale of a dozen F-35Bs as well as associated equipment and support services for $2.75 billion. The notification specifies the initial sale of four aircraft with options for eight additional aircraft. Singapore will conduct training at Ebbing Air National Guard Base in Fort Smith, Arkansas. The country currently operates the most capable air force in Southeast Asia with 40 F-15SGs and 60 F-16C/D Block 52s.

Switzerland

On June 30, 2021, Switzerland announced the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter as its future combat aircraft after a completive evaluation against Boeing’s F/A-18 Super Hornet, the Eurofighter Typhoon and the Dassault Rafale. Lockheed’s bid for 36 F-35As was viewed as having best aircraft in terms of effectiveness, product support and international cooperation. Switzerland scored the F-35 offer at 336 points; 95 points higher than any other entrants. Each type was scored against its effectiveness, weighted at 55%, product support: 25%, cooperation: 10% and direct offset: 10%. Scores for the other contenders have not yet been published. Next steps will see the Swiss Council of Ministers – the country’s cabinet – go to Parliament to get the F-35 purchase approved, this is likely to come in 2022 when the national armaments program is discussed. Switzerland hopes to begin deliveries between 2025-2030 allowing the phase out of the Hornet by 2030.

Swiss analysis concluded that the F-35’s purchase and operating costs will be lower than the competition. Defense materiel agency, Armasuisse says the F-35 offer made in February [2021] is valued at 5.068 billion Swiss Francs (CHF), well under the Swiss budget cap for the fighter of CHF6 billion, they also state that the procurement and operating costs add up to CHF15.5 billion over 30 years, some 2 billion less than the second lowest bidder. Darko Savic, Head of New Fighter Aircraft section at Armasuisse said his agency had been given “binding information” on the costs per flight hour, stating that these equated to between CHF55,000-CHF60,000. The evaluation also states that 20 percent fewer flying hours are required than with the other candidates with more training to be done in simulators. Other factors which may have influenced lower costs include the improved relatability of Block 4 aircraft and using nine instead of 12 maintainers similar to Belgium’s F-35 sustainment model.

While the F-35 scored highly in terms of effectiveness, product support and international cooperation, the evaluation states the F-35 proposal fell down in terms of its direct offset offer, the evaluation stating that the Lockheed Martin offer “does not achieve direct offset at the time of submitting the offer,” however it notes that the company has four years after the last delivery to completely fulfil offset obligations. Swiss requirements call for 60% of fighter contract value to be offset.

It is unclear whether Lockheed Martin’s proposal for limited local assembly of four F-35s by local company RUAG Aerospace will be taken up. The Swiss tender did not require local assembly but allows the bidder teams to propose options to improve the country’s ability to sustain the aircraft autonomously. Lockheed Martin had also proposed work packages for Swiss companies to produce 400 shipsets of canopies and transparencies for the global F-35 fleet and to establish a regional hub to maintain, repair and overhaul them for European operators. The company also has proposals for a so-called F-35 cyber center of excellence which the company says will allow it to fulfil Swiss requirements to operate the F-35 securely and autonomously. Switzerland also has the option to have its F-35s built at the Cameri Final Assembly and Check Out facility in Italy, just 25 miles from the Swiss border.

As well as the F-35 decision, Bern also selected Raytheon’s Patriot air defense system for the ground-based element of the Air2030 program, the U.S.-built system winning out against the EuroSam SAMP/T. Switzerland now plans to purchase five Patriot fire units, with a procurement cost of CHF1.97 billion, squeezing into the budget cap of CHF2 billion. The Swiss evaluation of Patriot mirrored that of F-35, finding the system to be not cheaper to operate than the European SAMP/T, but would also be more effective. The Patriot offer was made in conjunction with Switzerland-based Rheinmetall Air Defense and Mercury Systems. Officials insist that the choice of the two U.S.-developed systems does not mean that the country has turned its back on Europe, noting that numerous other European countries have adopted the F-35 including neighbors Italy.

The selection has come has a surprise to observers however particularly as Swiss Air Force mission is primarily one of policing the airspace of the landlocked neutral country. Bern has never sent fighter aircraft to support international missions nor do its pilots routinely practice ground attack or strike missions, apart from strafing. The selection looks set to face friction from opposition parties, with one describing the choice of F-35 as “completely incomprehensible,” hinting they could call for a referendum on the decision. The Swiss government barely scraped through approval to purchase new fighters in a referendum held last September. Just 50.1% of voters gave their backing to a fighter procurement, a lead of just under 9,500 people, from a turnout of 3.2 million, 59% of the country’s voters.

Turkey

Turkey had planned to buy 100 F-35s to replace its F-4s for $16 billion. As of July 16, 2019, the Trump Administration terminated Turkey’s involvement with the F-35 program in response to the country’s purchase, and acceptance of, the Russian S-400 Surface-to-Air Missile (SAM) system. Turkey signed a $2.5 billion contract with Russia for four batteries of S-400s in December 2017. The DoD plans to completely unwind Turkish industrial participation in F-35 production by March of 2020. Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, Ellen Lord, announced that shifting Turkish suppliers to U.S. sources would cost approximately $500 to $600 million. As of the time of this writing, six Turkish F-35s have been delivered to the U.S. Air Force.

Historical Participation

Turkey joined the F-35 program in June 2002 as a level three partner, contributing $175 million ($245 million in 2018 dollars) toward the development of the aircraft. On May 6, 2014, the government directed the country's Undersecretariat for Defense Industries (SSM) to order the first two aircraft as part of LRIP 10 which were delivered in June 2018. Turkey’s first F-35 took flight in August 2018.

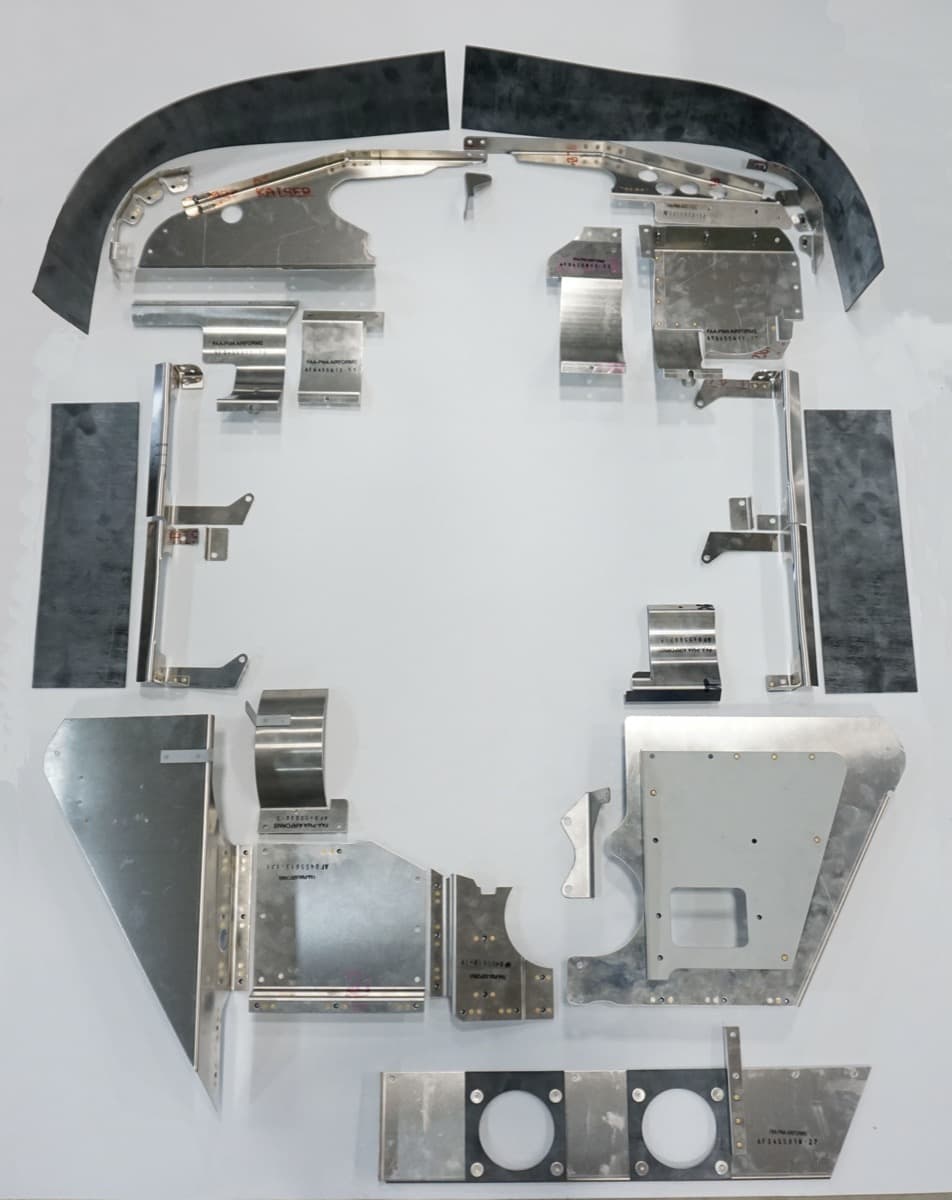

Turkish industrial participation comprised ten companies and was expected to reach $12 billion over the life of the program. TAI was be responsible for the largest share of Turkish industrial participation. TAI produced center fuselages – in support of Northrop Grumman, composite skins, weapon bay doors and fiber placement composite air inlet ducts for the F-35. TAI also produced 45% of all the F-35’s air-to-ground pylons.

Ankara had also approved establishment of a final assembly and checkout and depot-level maintenance facility for the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine in the country. On Dec. 11, 2014, the JPO announced the installation would serve as the primary location for heavy engine maintenance for European JSFs.

Lockheed Martin was also teaming with Ankara-based Roketsan to codevelop the SOM-J medium-range cruise missile for internal carriage on the F-35. The 1,000-lb. weapon is based on the larger SOM standoff cruise missile developed indigenously in Turkey for external carriage on fighters. The turbojet-powered weapon has a range of more than 100 nm against stationary or moving targets on land or sea. Navigation is by GPS and a terrain image-matching system. An imaging infrared seeker provides terminal guidance and a weapons data link will be added to the SOM-J for use against moving targets. Integration of the 1000-lb. weapon was planned for 2023 as part of the Block 4 upgrade.

United Arab Emirates

In 2009 the UAE expressed an initial interest in the F-35 at an event held on the eve of the 2009 Dubai Air Show. The DoD opened talks with the UAE about a possible sale in late 2017, but the talks led to nothing. Following the signing of the Abraham Accords in August 2020 in which the UAE formally recognized Israel, the DSCA issued a notification regarding the potential sale of 50 F-35As along with associated equipment and support services for $10.4 billion. The Senate held a vote to disapprove of the sale in December which failed 47-49. An LOA was subsequently signed on the last full day of the Trump Administration on Jan. 20, 2021. The Biden Administration subsequently announced it would conduct a review of the sale. Even if the sale proceeds, the UAE is unlikely to receive its first aircraft prior to 2025 given existing allotments of production capacity.

In October 2021, the State Department responded to and Aviation Week media inquiry and stated, "Projected delivery dates on the sales, if implemented, would be several years in the future… Thus we anticipate a robust and sustained dialogue with the UAE to ensure that any defense transfers meet our mutual strategic objectives to build a stronger, interoperable, and more capable security partnership, while protecting U.S. technology". The Biden administration has expressed concern over the UAE's growing commercial, diplomatic and military ties to China - including Huawei infrastructure and a clandestine attempt by China to build a military facility at Jebel Ali. In December 2021, the UAE signed a €14 billion ($15.8) contract for 80 Rafale F4s as well as €2 billion ($2.25 billion) in associated munitions. The purchase has been under consideration since 2008 is not related directly to the F-35 and fulfills the Gulf nation's long-standing requirement to replace its 58 Mirage 2000-5s and maintain a dual sourced fighter force. U.S. media outlets reported the UAE withdrew its LOA for the F-35, MQ-9 and weapons package shortly after the arm deal was finalized. The U.S. strategy appears to be pushing for the UAE to make a clear break in its China relationship, well beyond Huawei investments, as a precondition for the F-35 sale. The UAE is signaling that such a precondition is politically unacceptable.

United Kingdom

The U.K.'s current program of record calls for "at least 48 F-35Bs" down from the original POR of 138. The UK's Integrated Review guidance released in March 2021 detailed a series of cuts to the UK's combat forces, including the F-35, Eurofighter Typhoon, C-130J and Hawk T1 trainer. Such cuts will pay for the Tempest next generation air combat system which is required to sustain the UK's aerospace industrial base into the 2040s. In March 2021, the First Sea Lord Adm. Tony Radakin stated the UK's final F-35 POR could be within the range of 60-80 aircraft. British aircraft delivered before the end of 2017 will be delivered with the Block 3i software. Follow-on aircraft will arrive with Block 3F software, which will allow the U.K. to employ the ASRAAM as well as the Paveway IVGPS/INS/laser-guided bomb. Later, London plans to integrate additional weapons on its F-35s, including MBDA’s Meteor long-range AAM and the Selective Precision Effects at Range (SPEAR) 3 networked precision-guided weapon. In June 2020, the UK's Minister of State for Defence Procurement stated all F-35s would be brought up to the Block 4 configuration. UK cost estimates could be as high as £22 million per airframe ($30 million).

The UK began studies to replace its Harrier fleet in the 1990s leading up to formally joining the F-35 program in 1995. The UK signed an MOU to fund 10% of the concept development phase or $200 million. The UK invested an additional $2 billion during the System Development Demonstration (SDD) phase. Originally the UK planned to acquire 150 F-35s but revised its procurement goal to 138 aircraft in 2002. The UK ordered its first F-35B as part of LRIP 4 with subsequent orders following in LRIP 8 and beyond. 617 Sqn reformed in April 2018 as the Lightning Force transitions aircraft from U.S. based training and qualification missions to operational service at RAF Marham, Norfolk. In September 2018, the UK conducted carrier take-off and landing tests off the coast of Maryland. The second squadron, 809 Naval Air Squadron, will also be home-based at RAF Marham. The U.K. MoD has confirmed it will build three landing pads at RAF Marham capable of dealing with vertical landings by the F-35B. In January 2019, the UK declared IOC for land operations of the F-35B. The HMS Queen Elizabeth embarked for its first operational deployment with UK and USMC F-35s for the first time in May 2021. As of December 2021, the Lightning Force operates 23 aircraft following the loss of a single airframe in November 2021.

The UK is the only Tier One partner in the JSF program. A total of 15% of the value of each F-35 is manufactured in the UK. As of July 2018, the UK has received $13.55 billion in contracts related to F-35 production, supporting more than 20,000 jobs. BAE Systems manufactures the aft fuselage, horizontal and vertical tails, fuel system and EW system.

Upgrades

Block Upgrades

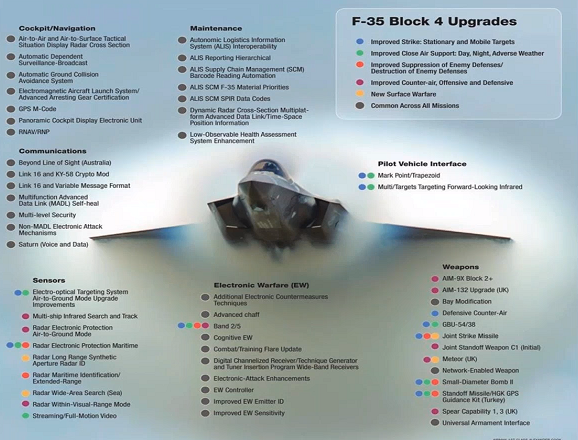

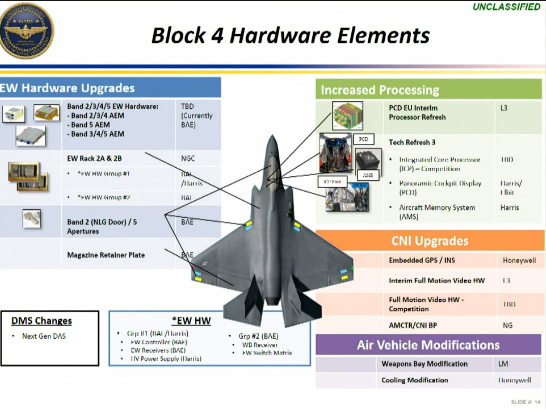

The Block 4 is the first substantial series of upgrades after Block 3F – the IOC warfighting configuration. The Block 4 program is projected to cost $14 billion to develop through FY2027 and will be rolled out incrementally in production Lots 15 (FY2023), Lot 16 (FY2024) and 17 (FY2025) in four distinct configurations: Block 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4. Of these, Block 4.2 and Block 4.4 are hardware modifications and 4.1 and 4.3 are software only. Hardware modifications of in-service aircraft will follow one year after production of that configuration e.g. Lot 15 new build FY2023 and modification of existing aircraft in FY2024. The USAF will modify 148 Lot 5-10 to the Lot 15 configuration and 335 Lot 11-16 aircraft to the Lot 17 configuration. Accompanying Block 4, smaller upgrades will be fielded in six-month cycles under the Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) process. The FY22 budget describes the following Lot associated Block 4 configurations:

FY2021 (Lot 13) - Magazine Retainer Plate - Chaff and Flare Magazine Retainer Plate - provides the capability for programmable expendables, programmable magazine load-outs, programmable emergency jettison and quicker inventory

FY2024 (Lot 15) - Technical Refresh 3 (TR3), Next Generation Distributed Aperture System (Next Gen DAS), Cooling Mod, and Advanced Communication, Navigation, Identification Processor